An Example of Rust's Fearless Concurrency

Rust is famous for its "fearless concurrency." It's a bold claim, but what does it actually mean? How does Rust let you write concurrent code without constantly battling race conditions? ast-grep's recent refactor is a great example of Rust's concurrency model in action.

Old Architecture of ast-grep's Printer

ast-grep is basically a syntax-aware grep that understands code. It lets you search for specific patterns within files in a directory. To make things fast, it uses multiple worker threads to churn through files simultaneously. The results then need to be printed to the console, and that's where our concurrency story begins.

Initially, ast-grep had a single Printer object, shared by all worker threads. This was designed for maximum parallelism – print the results as soon as you find them! Therefore, the Printer had to be thread-safe, meaning it had to implement the Send + Sync traits in Rust. These traits are like stamps of approval, saying "this type is safe to move between threads (Send) and share between threads (Sync)."

trait Printer: Send + Sync {

fn print(&self, result: ...);

}

// demo Printer implementation

struct StdoutPrinter {

// output is shared between threads

output: Mutex<Stdout>,

}

impl Printer for StdoutPrinter {

fn print(&self, result: ...) {

// lock the output to print

let stdout = self.output.lock().unwrap();

writeln!(stdout, "{}", result).unwrap();

}

}And Printer would be used in worker threads like this:

// in the worker thread

struct Worker<P: Printer> {

// printer is shareable between threads

// because it implements Send + Sync

printer: P,

}

impl<P> Worker<P> {

fn search(&self, file: &File) {

let results = self.search_in_file(file);

self.printer.print(results);

}

// other methods not using printer...

}While this got results quickly, it wasn't ideal from a user experience perspective. Search results were printed all over the place, not grouped by file, and often out of order. Not exactly user-friendly.

Migrate to Message-Passing Model

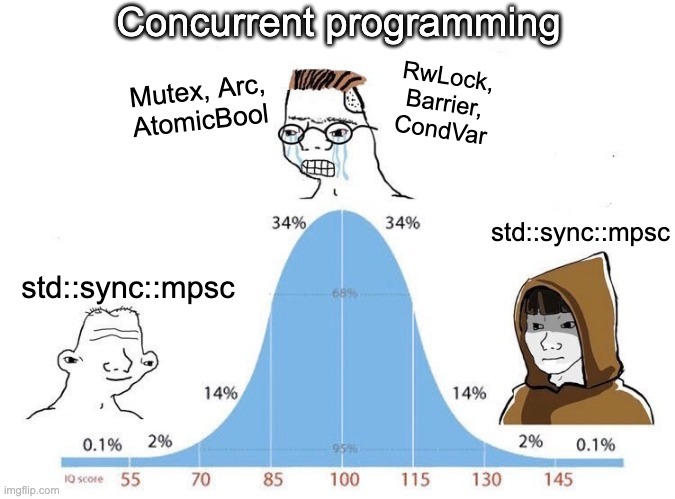

The architecture needed a shift. Instead of sharing a printer, we moved to a message-passing model, using an mpsc channel. mpsc stands for Multi-Producer, Single-Consumer FIFO queue, where a Sender is used to send data to a Receiver.

Now, worker threads would send search results to a single dedicated printer thread. This printer thread then handles the printing sequentially and neatly.

Here's the magic: because the printer is no longer shared between threads, we could remove the Send + Sync constraint! No more complex locking mechanisms! The printer could be a simple struct with a mutable reference to the standard output.

Here are some more concrete changes we made:

Remove Generics

The printer used to be a field of Worker. Now, we had to move it out to the main thread.

struct Worker {

sender: Sender<...>,

}

impl Worker {

fn search(&self, file: &File) {

let results = self.search_in_file(file);

self.sender.send(results).unwrap();

}

// other methods, no generic used

}

fn main() {

let (sender, receiver) = mpsc::channel();

let mut printer = StdoutPrinter::new();

let printer_thread = thread::spawn(move || {

for result in receiver {

printer.print(result);

}

});

// spawn worker threads

}So, what did we gain? Smaller binary size.

Previously, the worker struct was generic over the printer trait, which meant that the compiler had to generate code for each printer implementation. This resulted in a larger binary size. By removing generics over the printer trait, the worker struct no longer needs multiple copies.

Remove Send + Sync Bounds

The Send + Sync bounds on the printer trait were no longer needed. The CLI changed the printer signature to use a mutable reference instead of an immutable reference.

In the previous version, we couldn't use &mut self because it cannot be shared between threads. So we had to use &self and wrap the output in a Mutex. Now we can simply use a mutable reference since it is no longer shared between threads.

trait Printer {

fn print(&mut self, result: ...);

}

// stdout printer implementation

struct StdoutPrinter {

output: Stdout, // no more Mutex

}

impl Printer for StdoutPrinter {

fn print(&mut self, result: ...) {

writeln!(self.output, "{}", result).unwrap();

}

}Without the need to lock the printer object, the code became faster in a single thread, without data-racing.

Thanks to Rust, this big architectural change was relatively painless. The compiler caught all the places where we were trying to share the printer between threads. It forced us to think about the design and make the necessary changes.

What Rust Teaches Us

This experience with ast-grep really highlights Rust's approach to concurrency. Rust forces you to think deeply about your design and encode it in the type system.

You can't just haphazardly add threads and hope it works. Without clearly designing the process architecture upfront, you will soon find yourself trapped in a maze of the compiler's error messages.

Rust then forces you to express the concurrency design in code via type system enforcement. You need to use concurrency primitives, ownership rules, borrowing, and the Send/Sync traits to encode your design constraints. The compiler acts like a strict project manager, not allowing you to ship code if it doesn't meet the concurrency requirements.

In other languages, concurrency is often treated as an afterthought. It is up to the programmer's discretion to design the architecture correctly. And it is also the programmer's responsibility to conscientiously and meticulously ensure the architecture is correctly implemented.

The Trade-off of Fearless Concurrency

And what, Rust, must we give in return? Rust's approach comes with a trade-off:

- Upfront design investment: You need to design your architecture thoroughly before you start writing actual production code. While the compiler could be helpful when you explore options or ambiguous design ideas, it can also be a hindrance when you need to iterate quickly.

- Refactoring can be hard: If you need to change your architectural design, it can be an invasive change across your codebase, because you need to change the type signatures, the concurrency primitives, and data flows. Other languages might be more flexible in this regard.

Rust feels a bit like a mini theorem prover, like Lean. You are using the compiler to prove that your concurrent model is correct and safe.

If you are still figuring out your product market fit and need rapid iteration, other languages might be a better choice. But if you need the safety and performance that Rust provides, it is definitely worth the effort!

The Fun to Play with Rust

ast-grep is a hobby project. Even though it might be a bit more work to get started, this small project shows that building concurrent applications in Rust can be fun and rewarding. I hope this gave you a glimpse into Rust's fearless concurrency and maybe inspires you to take the plunge!