How to Debug ast-grep Rule Effectively

Let Claude Debug For You

If you prefer not to debug manually, try the ast-grep Claude skill. It can explain AST structures, identify why rules don't match, and suggest fixes—all through natural conversation.

Debugging ast-grep rules can be frustrating. You write what looks like a perfectly reasonable rule, test it against your code, and... nothing matches. Or worse, it matches things you didn't expect.

The key to effective debugging is one word: SIMPLIFY.

When your rule doesn't work, resist the urge to add more conditions or make the pattern more complex. Instead, strip everything down to the basics and build back up systematically. This post will teach you a reliable debugging workflow that works for any ast-grep rule.

The Debugging Workflow

Here's a step-by-step process to debug any ast-grep rule:

Set up a reproducible test case. Use

ast-grep scan -r test.yml test.fileor the online playground to quickly iterate on your code and rule.Reduce the code to a minimal example. Delete everything unrelated to the rule. If your rule should match a function call, remove all the surrounding code until you have just the essential lines.

Inspect the AST structure. Use

ast-grep run -p '{code}' -l {lang} --debug-query=cstor the playground's AST view to understand the actual tree structure. The AST often looks different from what you'd expect.Simplify the rule. Remove rule conditions one by one. Test each simpler version to see what actually matches. Pay attention to how meta-variables are being captured.

Repeat steps 2-4. Continue simplifying both code and rule until you isolate the issue.

Let's see this workflow in action with real examples.

Example 1: The SQL Injection Detector

Consider this rule designed to detect potential SQL injection vulnerabilities in Python:

id: some_sqli_rule

language: python

rule:

pattern: $X.execute($$$)

has:

kind: argument_list

has:

nthChild: 1

any:

- kind: identifier

pattern: $VAR

- has:

stopBy: end

kind: identifier

pattern: $VAR

inside:

stopBy: end

kind: module

has:

stopBy: end

kind: assignment

pattern: $VAR = $$$The rule should flag cases where a variable assigned from user input is passed to execute(). Let's test it against this code:

def test_sql_injection_detection():

"""Test case for static analysis tools detecting SQL injection vulnerabilities"""

# Setup test database

db = DatabaseManager(':memory:')

user_input = req.query.param

vuln_param = compute_based_on_input(user_input)

db.execute(f"DROP TABLE IF EXISTS {vuln_param}") # Vulnerable, but not detected!No match. Why?

Step 1: Reduce to Minimal Code

Let's strip the code down to the essentials:

something = "value"

vuln_param = other

x.execute(f"DROP TABLE IF EXISTS {vuln_param}") # Still no matchInterestingly, if we remove the first assignment:

vuln_param = other

x.execute(f"DROP TABLE IF EXISTS {vuln_param}") # This matches!Now it matches! The presence of something = "value" somehow breaks the rule. This is our first clue.

Step 2: Simplify the Rule

Let's test individual parts of the rule. First, just the has portion:

rule:

pattern: $X.execute($$$)

has:

kind: argument_list

has:

nthChild: 1

any:

- kind: identifier

pattern: $VAR

- has:

stopBy: end

kind: identifier

pattern: $VARThis matches! And it captures $VAR as vuln_param.

Now let's test just the inside portion:

rule:

pattern: $X.execute($$$)

inside:

stopBy: end

kind: module

has:

stopBy: end

kind: assignment

pattern: $VAR = $$$This also matches! But wait—what does it capture $VAR as?

Step 3: Identify the Conflict

Here's the problem: when we have both assignments in the code, the inside rule matches $VAR to something (the first assignment it encounters), while the has rule expects $VAR to be vuln_param.

Since something ≠ vuln_param, the combined rule fails.

This is due to rule matching order sensitivity. In YAML, sibling keys are processed in an implementation-defined order. The inside rule executes first, binding $VAR to something, so the subsequent has rule cannot match.

Step 4: The Fix

Use all to explicitly control the matching order:

id: some_sqli_rule

language: python

rule:

pattern: $X.execute($$$)

all:

- has:

kind: argument_list

has:

nthChild: 1

any:

- kind: identifier

pattern: $VAR

- has:

stopBy: end

kind: identifier

pattern: $VAR

- inside:

stopBy: end

kind: module

has:

stopBy: end

kind: assignment

pattern: $VAR = $$$By putting has before inside in the all array, we ensure $VAR is first bound to the identifier in the execute call, and then we verify that this same variable was assigned earlier.

Inspecing the playground now shows the correct match!

Example 2: The Missing Case Statement

Here's another puzzling case. This rule should find case statements that don't contain assert(false):

rule:

kind: case_statement

not:

has:

pattern: assert($A)

has:

kind: 'false'

stopBy: end

stopBy: endTest code:

switch (Mychar) {

[[likely]] case '1': { assert(OtherVar > 1); }

[[unlikely]] case '2': { assert("2" && false); }

[[unlikely]] case '3': { assert("3" && true); }

[[unlikely]] case '4': { assert("" && true); }

}Expected: Match cases '1', '3', and '4' (they don't have assert(false)).

Actual: Only cases '3' and '4' are matched. Case '1' is missing. Why?

Step 1: Find All Case Statements

First, let's see what case_statement nodes exist:

ast-grep scan --inline-rules "id: all-cases

language: cpp

rule:

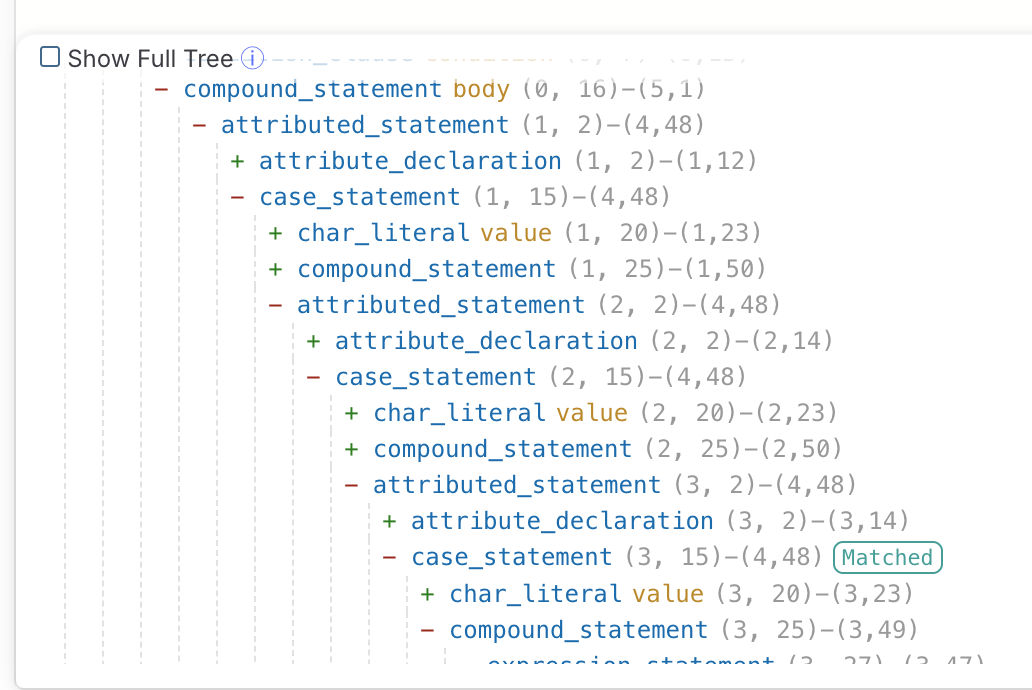

kind: case_statement" test.cppThe output reveals something surprising. Each match shows the range of the node:

- Case '1': spans lines 2-5 (includes cases 2, 3, and 4!)

- Case '2': spans lines 3-5 (includes cases 3 and 4)

- Case '3': spans lines 4-5 (includes case 4)

- Case '4': spans line 5 only

Step 2: Understand the AST Structure

In C/C++ tree-sitter grammar, case_statement nodes are nested. Each case statement contains all subsequent case statements as descendants. This is how tree-sitter represents the fall-through semantics of C switch statements.

case '1' node

├── { assert(OtherVar > 1); }

└── case '2' node ← nested inside case '1'!

├── { assert("2" && false); }

└── case '3' node ← nested inside case '2'!

├── { assert("3" && true); }

└── case '4' node ← nested inside case '3'!

└── { assert("" && true); }You can also use playground to visualize the AST structure.

Step 3: Identify the Problem

Now the issue is clear. When our rule checks case '1':

- It looks for

kind: case_statement✓ - It checks

not: has: ... kind: 'false'— does case '1' have a descendant with kindfalse?

Since case '2' is nested inside case '1', and case '2' contains assert("2" && false), the false keyword IS a descendant of case '1'!

The not: has: condition fails because false exists somewhere in the subtree. Case '1' is incorrectly excluded.

Step 4: The Fix

To fix this, we need to restrict the search to only the immediate body of each case, not its nested case statements. We can use stopBy to stop at the next case:

rule:

kind: case_statement

not:

has:

pattern: assert($A)

has:

kind: 'false'

stopBy: end

stopBy:

kind: case_statementBy setting stopBy: { kind: case_statement }, the has search stops when it encounters another case statement, preventing it from looking into nested cases.

The Lesson

When a rule unexpectedly fails to match:

- Don't assume the AST matches your mental model — C/C++ case statements nest!

- Always inspect the actual node ranges, not just the source text

- Use

stopByto control how deep relational rules search

Key Takeaways

Simplify, don't complicate. When debugging, remove code and rule conditions until you find the minimal failing case.

Trust the AST, not the source. The AST structure can surprise you. Always verify with

--debug-query=cstor the playground.Watch meta-variable bindings. When using the same meta-variable in multiple places, order matters. Use

allto control matching order.Iterate systematically. Don't guess. Remove one thing at a time, test, observe, repeat.

Use the right tools. The online playground provides instant feedback and AST visualization. Use it liberally.

Happy debugging!